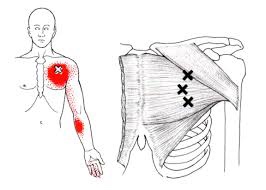

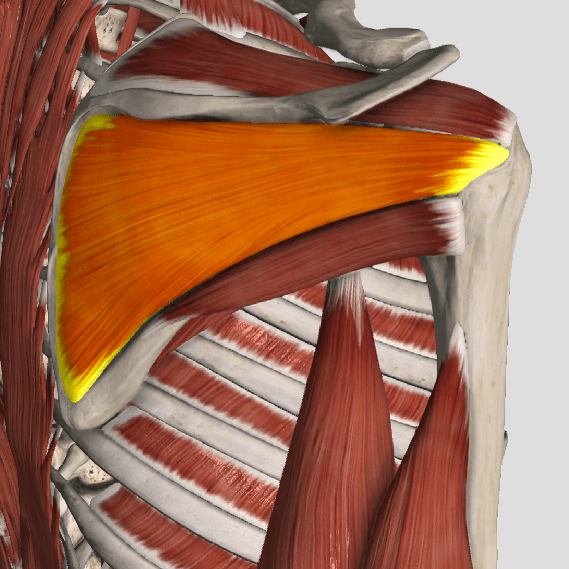

Your biceps muscle attaches to your shoulder through two strong fibrous bands called “tendons.” The term “biceps tendinitis” means that one of these bands has become painfully irritated from strain or degeneration. Sometimes the tendon may be strained by an accident or lifting injury. Biceps tendinitis more often results from repeated pinching of the tendon beneath the bony part of your shoulder

from a condition called “impingement.” Repeated overhead activity, like throwing, swimming, gymnastics, and racquet sports are known culprits. Biceps tendinitis is often accompanied by other conditions, like rotator cuff tears or injuries to the cartilage around the rim of your shoulder joint. Factors that make you more likely to develop biceps tendinitis include: improper lifting techniques, inflexibility, poor posture, or repetitive overloading.

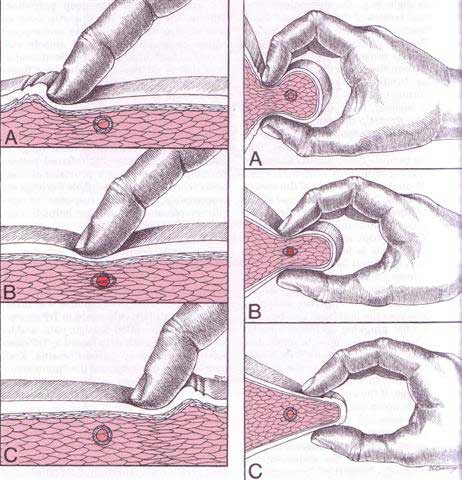

Your symptoms likely include a deep, throbbing ache over the front of your shoulder. The pain often refers toward the outside of your arm. The main job of your biceps muscle is to flex your elbow and turn your palm up, so overhead movements or activities that require flexion of your elbow may cause pain. Patients often report increased discomfort when initiating activity. Night time symptoms are common, especially if you lie on your affected shoulder. Be sure to tell your doctor if you notice popping, catching, or locking during movements, as this may suggest an additional problem. A painful, loud “pop” followed by relief with a visible bulge in your biceps (Popeye deformity) suggests that your tendon has ruptured.

Surgery is rarely required for biceps tendon problems unless you are a young athlete or worker who performs exceptionally heavy physical activity and have completely ruptured your tendon. The most effective treatment for the majority of biceps tendinitis patients is conservative care, like the type provided in our office. Initially, you may need to avoid heavy or repetitive activity, (especially overhead activity and elbow flexion) as returning to activity too soon may prolog your recovery. You should specifically avoid military presses, upright rows, and wide grip bench presses until cleared by your doctor. You may use ice over your shoulder for 10-15 minutes at a time each hour. The exercises described below will be a very important part of your recovery and should be performed consistently.