fitness

Regular Exercise Reduces Cancer, Dementia, Stroke, and Heart Disease Risks

Exercise: More Health Benefits of Exercise Revealed.

Experts from the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges analyzed more than 200 pieces of research and found that regular exercise can reduce breast cancer risk by 25%, bowel cancer risk by as much as 45%, dementia and stroke risk by 30%, and the chance of developing heart disease by over 40%. Researcher Dr. John Wass adds, “The results from this report reinforce previous findings that regular physical activity of just 30 minutes, 5 times a week, can make a huge difference to a patient’s health.” Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, February 2015

Promoting Physical Activity Among American Youth: Evidence-Based Strategies

The 2014 study underscores a concerning trend among American youth, revealing that the majority fail to meet the federally recommended guideline of 60 minutes of daily physical activity. In response to this pressing public health concern, the study offers a range of actionable strategies aimed at facilitating children’s attainment of the recommended activity goals.

One proposed intervention is the implementation of mandatory daily physical education classes in schools, ensuring that children have regular opportunities to engage in structured physical activity throughout the school day. Additionally, integrating classroom-based physical activity breaks into academic curriculum can inject bursts of movement into sedentary periods, fostering an active learning environment.

Encouraging alternative modes of transportation, such as walking or biking to school, not only promotes physical activity but also reduces reliance on motor vehicles, contributing to environmental sustainability. Moreover, renovating community parks to include a diverse array of equipment and activity opportunities can transform outdoor spaces into vibrant hubs of recreational activity, enticing children to engage in active play.

The study also advocates for the expansion of after-school physical activity programs, providing children with structured opportunities for exercise and socialization beyond the school day. Furthermore, modifying school playgrounds to incorporate features that facilitate active play can empower children to engage in spontaneous physical activity during recess and leisure time.

Lead author Dr. David Bassett emphasizes the importance of leveraging these evidence-based strategies to inform policy decisions and initiatives aimed at promoting physical activity among youth. By adopting a multifaceted approach that addresses environmental, educational, and recreational factors, stakeholders can collaboratively work towards creating a culture of active living that empowers children to lead healthy, physically active lifestyles.

American Journal of Preventive Medicine, March 2015

What Exercises Should I Do For Fibro?

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a very common, chronic condition where the patient describes “widespread pain” not limited to one area of the body. Hence, when addressing exercises for FM, one must consider the whole body. Perhaps one of the most important to consider is the squat.

If you think about it, we must squat every time we sit down, stand up, get in/out of our car, and in/out of bed. Even climbing and descending steps results in a squat-lunge type of movement.

The problem with squatting is that we frequently lose (or misuse) the proper way to do this when we’re in pain as the pain forces us to compensate, which can cause us to develop faulty movement patterns that can irritate our ankles, knees, hips, and spine (particularly the low back). In fact, performing a squatting exercise properly will strengthen the hips, which will help protect the spine, and also strengthens the glutel muscles, which can help you perform all the daily activities mentioned above.

The “BEST” type of squat is the free-standing squat. This is done by bending the ankles, knees, and hips while keeping a curve in the low back. The latter is accomplished by “…sticking the butt out” during the squat.

Do NOT allow the knees to drift beyond your toes! If you notice sounds coming from your knees they can be ignored IF they are not accompanied by pain. If you do have pain, try moving the foot of the painful knee about six inches (~15 cm) ahead of the other and don’t squat as far down. Move within “reasonable boundaries of pain” by staying away from positions that reproduce sharp, lancinating pain that lingers upon completion.

Hamstring Problems?

A great injury prevention movement is the glute-ham raise. Done after a warm up and prior to competition it will significantly reduce the odds of hamstring strains in running athletes in sports like Soccer, Football and Sprinting.

To perform the movement:

Begin in a tall kneeling position on a cushion or pillow.

Partner grabs and holds ankles to ground or hook your feet under a stable surface.

Keeping your torso neutral and your thighs in line with your body, bend forward at the knees, using your hamstrings to control the speed of your forward bend.

Go as far as you can without cramping, pain or falling to the ground.

My Hip Hurts….

One of the structures that is frequently blamed for hip pain is called the labrum—the rubbery tissue that surrounds the socket helping to stabilize the hip joint. This tissue often wears and tears with age, but it can also be torn as a result of a trauma or sports-related injury.

The clinical significance of a labral tear of the hip is controversial, as these can be found in people who don’t have any pain at all. We know from studies of the intervertebral disks located in the lower back that disk herniation is often found in pain-free subjects—between 20-50% of the normal population. In other words, the presence of abnormalities on an MRI is often poorly associated with patient symptoms, and the presence of a labral tear of the hip appears to be quite similar.

For instance, in a study of 45 volunteers (average age 38, range: 15–66 years old; 60% males) with no history of hip pain, symptoms, injury, or prior surgery, MRIs reviewed by three board-certified radiologists revealed a total of 73% of the hips had abnormalities, of which more than two-thirds were labral tears.

Another interesting study found an equal number of labral tears in a group of professional ballet dancers (both with and without hip pain) and in non-dancer control subjects of similar age and gender.

Another study showed that diagnostic blocks—a pain killer injected into the hip for diagnostic purposes to determine if it’s a pain generator—failed to offer relief for those with labral tears.

Doctors of chiropractic are trained to identify the origins of pain arising from the low back, pelvis, hip, and knee, all of which can mimic or produce hip symptoms. Utilizing information derived from a careful history, examination, imaging (when appropriate), and functional tests, chiropractors can offer a nonsurgical, noninvasive, safe method of managing hip pain.

Why Walk?

Why Does My Back Hurt?

What the heck is a trigger point?

What is a Trigger Point?

Trigger Points (TP’s) are defined as a “hyper-irritable spot within a taut band of skeletal muscle. The spot is painful on compression and can evoke characteristic referred pain and autonomic phenomena.”1

Put into plain language, a TP is a painful knot in muscle tissue that can refer pain to other areas of the body. You have probably felt the characteristic achy pain and stiffness that TP’s produce, at some time in your life.

TP’s were first brought to the attention of the medical world by Dr. Janet G. Travell. Dr. Travell, physician to President John F. Kennedy, is the acknowledged Mother of Myofascial Trigger Points. In fact, “Trigger Point massage, the most effective modality used by massage therapists for the relief of pain, is based almost entirely on Dr. Travell’s insights.”2 Dr. Travell’s partner in her research was Dr. David G. Simons, a research scientist and aerospace physician.

Trigger Points are very common. In fact, Travell and Simons state that TP’s are responsible for, or associated with, 75% of pain complaints or conditions.1 With this kind of prevalence, it’s no wonder that TP’s are often referred to as the “scourge of mankind”.

Trigger Points can produce a wide variety of pain complaints. Some of the most common are migraine headaches, back pain, and pain and tingling into the extremities. They are usually responsible for most cases of achy deep pain that is hard to localize.

A TP will refer pain in a predictable pattern, based on its location in a given muscle. Also, since these spots are bundles of contracted muscle fibres, they can cause stiffness and a decreased range of motion. Chronic conditions with many TP’s can also cause general fatigue and malaise, as well as muscle weakness.

Trigger Points are remarkably easy to get, but the most common causes are

TP’s (black X) can refer pain to other areas (red)

Sudden overload of a muscle

- Poor posture

- Chronic frozen posture (e.g., from a desk job), and

- Repetitive strain

Once in place, a TP can remain there for the remainder of your life unless an intervention takes place.

Trigger Points Not Well Known

With thousands of people dealing with chronic pain, and with TP’s being responsible for — or associated with — a high percentage of chronic pain, it is very disappointing to find that a large portion of doctors and other health care practitioners don’t know about TP’s and their symptoms.

Scientific research on TP’s dates back to the 1700’s. There are numerous medical texts and papers written on the subject.

But, it still has been largely overlooked by the health care field. This has led to needless frustration and suffering, as well as thousands of lost work hours and a poorer quality of life.

How Are Trigger Points Treated?

As nasty and troublesome as TP’s are, the treatment for them is surely straight-forward. A skilled practitioner will assess the individual’s pain complaint to determine the most likely location of the TP’s and then apply one of several therapeutic modalities, the most effective of which is a massage technique called “ischemic compression”.

Basically, the therapist will apply a firm, steady pressure to the TP, strong enough to reproduce the symptoms. The pressure will remain until the tissue softens and then the pressure will increase appropriately until the next barrier is felt. This pressure is continued until the referral pain has subsided and the TP is released. (Note: a full release of TP’s could take several sessions.)

Other effective modalities include dry needling (needle placed into the belly of the TP) or wet needling (injection into the TP). The use of moist heat and stretching prove effective, as well. The best practitioners for TP release are Massage Therapists, Physiotherapists, and Athletic Therapists. An educated individual can also apply ischemic compression to themselves, but should start out seeing one of the above therapists to become familiar with the modality and how to apply pressure safely.

1 Simons, D.G., Travell, D.G., & Simons, L.S. Travell and Simons’Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: the Trigger Point Manual.

Vol. 1. 2nd ed. Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins, 1999.

PFPS Cont. You want details?

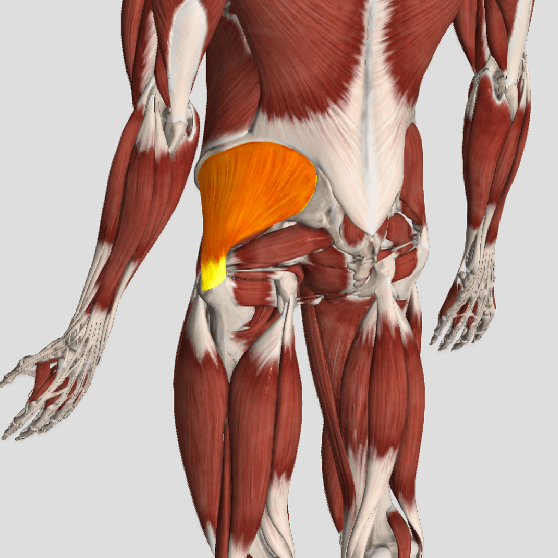

The muscles of the hip provide not only local stability, but also play an important role in spinal and lower extremity functional alignment. (1-4) While weakness in some hip muscles (hip extensors and knee extensors) is well tolerated, weakness or imbalance in others can have a profound effect on gait and biomechanical function throughout the lower half of the body. (5) Weakness of the hip abductors, particularly those that assist with external rotation, has the most significant impact on hip and lower extremity stability. (5,6)

The gluteus medius is the principal hip abductor. When the hip is flexed, the muscle also assists the six deep hip external rotators (piriformis, gemelli, obturators, and quadratus femoris). The gluteus medius originates on the ilium just inferior to the iliac crest and inserts on the lateral and superior aspects of the greater trochanter. While the principal declared action of the gluteus medius is hip abduction, clinicians will appreciate its more valuable contribution as a dynamic stabilizer of the hip and pelvis- particularly during single leg stance activities like walking, running, and squatting. The gluteus medius contributes approximately 70% of the abduction force required to maintain pelvic leveling during single leg stance. The remainder comes predominantly from 2 muscles that insert onto the iliotibial band: the tensor fascia lata and upper gluteus maximus. Hip abductor strength is the single greatest contributor to lower extremity frontal plain alignment during activity. (6)

Incompetent hip abductors and/or external rotators allows for excessive adduction and internal rotation of the thigh during single leg stance activities. This leads to a cascade of biomechanical problems, including pelvic drop, excessive hip adduction, excessive femoral internal rotation, valgus knee stress, and internal tibial rotation. (1,7-12)