What is a Trigger Point?

Trigger Points (TP’s) are defined as a “hyper-irritable spot within a taut band of skeletal muscle. The spot is painful on compression and can evoke characteristic referred pain and autonomic phenomena.”1

Put into plain language, a TP is a painful knot in muscle tissue that can refer pain to other areas of the body. You have probably felt the characteristic achy pain and stiffness that TP’s produce, at some time in your life.

TP’s were first brought to the attention of the medical world by Dr. Janet G. Travell. Dr. Travell, physician to President John F. Kennedy, is the acknowledged Mother of Myofascial Trigger Points. In fact, “Trigger Point massage, the most effective modality used by massage therapists for the relief of pain, is based almost entirely on Dr. Travell’s insights.”2 Dr. Travell’s partner in her research was Dr. David G. Simons, a research scientist and aerospace physician.

Trigger Points are very common. In fact, Travell and Simons state that TP’s are responsible for, or associated with, 75% of pain complaints or conditions.1 With this kind of prevalence, it’s no wonder that TP’s are often referred to as the “scourge of mankind”.

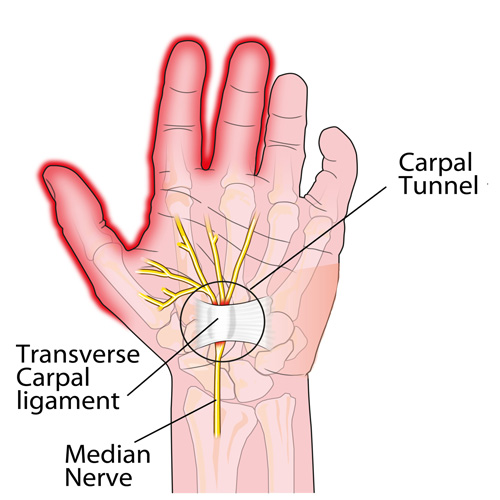

Trigger Points can produce a wide variety of pain complaints. Some of the most common are migraine headaches, back pain, and pain and tingling into the extremities. They are usually responsible for most cases of achy deep pain that is hard to localize.

A TP will refer pain in a predictable pattern, based on its location in a given muscle. Also, since these spots are bundles of contracted muscle fibres, they can cause stiffness and a decreased range of motion. Chronic conditions with many TP’s can also cause general fatigue and malaise, as well as muscle weakness.

Trigger Points are remarkably easy to get, but the most common causes are

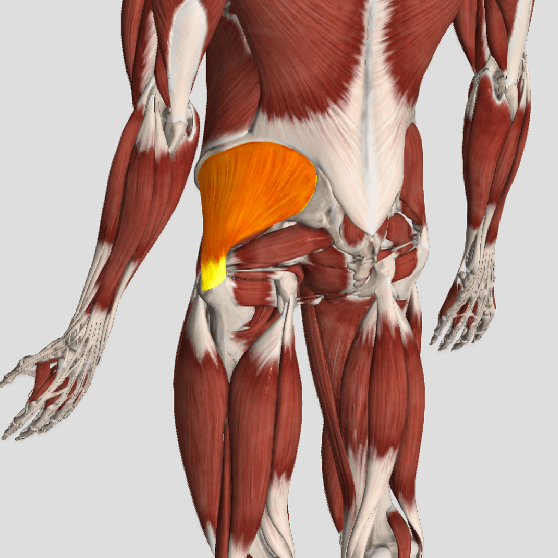

TP’s (black X) can refer pain to other areas (red)

Sudden overload of a muscle

- Poor posture

- Chronic frozen posture (e.g., from a desk job), and

- Repetitive strain

Once in place, a TP can remain there for the remainder of your life unless an intervention takes place.

Trigger Points Not Well Known

With thousands of people dealing with chronic pain, and with TP’s being responsible for — or associated with — a high percentage of chronic pain, it is very disappointing to find that a large portion of doctors and other health care practitioners don’t know about TP’s and their symptoms.

Scientific research on TP’s dates back to the 1700’s. There are numerous medical texts and papers written on the subject.

But, it still has been largely overlooked by the health care field. This has led to needless frustration and suffering, as well as thousands of lost work hours and a poorer quality of life.

How Are Trigger Points Treated?

As nasty and troublesome as TP’s are, the treatment for them is surely straight-forward. A skilled practitioner will assess the individual’s pain complaint to determine the most likely location of the TP’s and then apply one of several therapeutic modalities, the most effective of which is a massage technique called “ischemic compression”.

Basically, the therapist will apply a firm, steady pressure to the TP, strong enough to reproduce the symptoms. The pressure will remain until the tissue softens and then the pressure will increase appropriately until the next barrier is felt. This pressure is continued until the referral pain has subsided and the TP is released. (Note: a full release of TP’s could take several sessions.)

Other effective modalities include dry needling (needle placed into the belly of the TP) or wet needling (injection into the TP). The use of moist heat and stretching prove effective, as well. The best practitioners for TP release are Massage Therapists, Physiotherapists, and Athletic Therapists. An educated individual can also apply ischemic compression to themselves, but should start out seeing one of the above therapists to become familiar with the modality and how to apply pressure safely.

1 Simons, D.G., Travell, D.G., & Simons, L.S. Travell and Simons’Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: the Trigger Point Manual.

Vol. 1. 2nd ed. Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins, 1999.